This book takes a holistic view of supervision in the healthcare and social work fields and examines the developmental history, current theories, and research related to supervision skills. It is noted that while there is a large volume of research on supervision, there remains little agreement as to what constitutes ‘good’ supervision. This lack of conceptualization, compounded by the varying definitions, complexity of the activity, multi-layered relationships, and context variation has attributed to the difficulty in evaluating the effectiveness of supervision.

Historically, supervision was aimed at the new professional. Senior members of professions tended to reject the idea of supervision as they took it as a suggestion of incompetence. More recently, however, the importance of supervision, both to new members of the profession and to senior members, has been revitalized. Currently, interest in career long supervision is being shown in professions that historically only offered supervision as part of pre-service education.

Chapter two of this book highlights five models of supervision: (1) functional approaches, (2) developmental models, (3) reflective models, (4) post-modern approaches, and (5) cultural supervision models. The central model focused on in this book is the Reflective Learning Model of supervision. This model highlights supervision as a reflective learning process, as opposed to a process for direction and audit. The authors suggest that a reflective approach is “essential to affirm practitioners’ development, bringing together theory, tacit knowledge and transformative personal experience (18).”

Professional supervision has been found to provide three core functions which have remained fairly consistent over the years. These functions are administration, education, and support. Accountability to policies, protocols, ethics, and standards are addressed by the administrative function. Ongoing professional development and the resourcing of the supervisor are addressed by the educational function. Finally, the more personal aspects of the relationship between the practitioner and their work environment are addressed by the supportive function.

Developmental models of supervision are highly detailed and structured and consist of three categories: (1) those that offer linear stages of development, (2) those focused on process development models, and (3) lifespan developmental models (31). These models follow the basic premise “…that practitioners follow a predictable, staged path of development and that supervisors require a range of approaches and skills to attend to each sequential stage as it is achieved by the supervisee (31).”

Reflection is one of the four stages of experiential learning, but it is also considered an approach to supervision on its own. Reflective approaches to supervision “… focus on the whole experience and the many dimensions involved,” which include “… cognitive elements; feeling elements; meanings and interpretations from different perspectives (Fook & Garnder, 25 at 34).” Challenging assumptions and biases in order to change practice and aid individuals in understanding the connections between their public and private worlds is a goal of this model.

Post-modern supervision approaches are strengths-based, solution-oriented, language-centered, and identity-focused. This model requires supervisors to approach supervision through a social constructionist lens. This includes supervision that emphasizes the way the participants in professional encounters construct meaning; focusing on strengths rather than weaknesses; acknowledging that there are multiple perspectives rather than universal truths; operating in a less hierarchical manner; focusing on establishing collaborative approaches; and avoiding labelling individuals in a manner that highlights differences as deficits (36).

Finally, culturally based supervision considers how culture is relevant to the supervisor’s roles, style, and skills. The personal identity of both the supervisor and the supervisee form an integral part of the supervisory relationship. It has been posited that there are ideas and practices which are determined by cultural considerations, the supervisory context, and the prevailing culture which informs them. Further, it has been argued that “… any model of supervision is shaped by the cultural system in which it occurs (Tsai & Ho at 42).”

Cultural supervision is linked to personal, family, community, cultural, and professional domains. It has been stated that culturally centered models of supervision have been developed largely to address the broader social development of Indigenous and minority groups, while also being a response to social inequalities often experienced by marginalized communities. It has been suggested that supervisors should be trained in multicultural competency based on four dimensions:

- The awareness dimension (the supervisor must be aware of their own cultural and personal values, stereotypes, prejudices, and biases, as well as the differences between their values, communication styles, cognitive orientations, and emotional reactions and those of their supervisee);

- The knowledge dimension (facts and information about the history, research, worldviews, cultural codes, verbal and non-verbal language, and emotional expression);

- The relationship dimension (requires examination of supervision in cultural terms, including cultural identification, expectations, criticism, initiative, passivity, and roles); and

- The skills dimension (it is important to develop the ability to intervene in a culturally sensitive way) (Arkin at 44).

The book also discusses the role of power, trust, orientation toward learning, and continuing professional development within the supervisory relationship. The supervision relationship confers considerable authority on the supervisor and can potentially lead to an overly comfortable relationship with the supervisee. This may lead to poor exercise of authority, potentially amounting to collusion with the supervisee. This can result in poor and unsafe practices. Thus, conversations about the power relationship are integral to the supervisory relationship, as are discussions about personal power. The supervisory relationship should be malleable to the changing and developing needs of the supervisor and supervisee. Both parties should acknowledge mutuality in the relationship and adapt to students’ learning orientation.

Chapters 5 through 7 of this book address the ‘doing’ of supervision and identify skills that are essential to effective supervision. The Reflective Learning Model, outlined above, is highlighted. This model suggests that supervision is first and foremost a learning process (88). It is posited that this model of supervision promotes a way of thinking as opposed to a way of doing and allows supervisees to discover solutions on their own rather than being taught the correct solutions by the supervisors. This allows the supervisee to take responsibility for their own learning.

Characteristics and skills of a good supervisor are described and identified, and include:

- Competence and knowledge as practitioners;

- Competence as supervisors;

- An ability to challenge in a supportive manner;

- Openness to feedback;

- Ability to be self-monitoring;

- Ability to provide support and containment in a range of situations and emotions;

- An ability to manage power and authority; and

- To receive and value their own supervision.

In addition to the above noted characteristics and skills, it is important that the supervisors are adequately trained for their supervisory role.

Finally, this book explores the emotional aspects of supervision. It is noted that there are numerous barriers that prevent supervisors from exploring feelings. These barriers include the expectations and limitations of professional and organizational culture, fear of being overwhelmed by the supervisee’s feelings, fear of exposing their own inadequacies, and feeling exposed and vulnerable to public criticism.

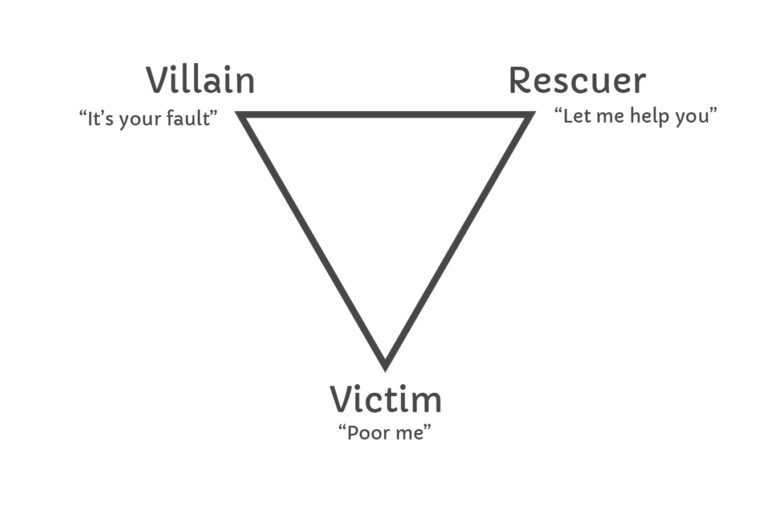

Supervision may prioritize risk management over attention to the practitioner’s own process and emotions. This is concerning because awareness of one’s own emotions facilitates an awareness and understanding of the emotions of others. The emotional impact within supervisory relationships, particularly those consisting of issues of inequality or power, may result in a ‘drama triangle’ (a model of dysfunctional social interactions), which consists of three roles: (1) villain; (2) rescuer; and (3) victim, as shown in the below diagram.

The drama triangle represents particular roles individuals hold in relation to others. The victim places responsibility and blame for situations onto the villain. The victim seeks a rescuer to save them from their unfair position. The villain does not consider themselves responsible and places blame for failure on the victim. These roles are in constant flux, rendering solutions unachievable and problematic interactions replete.

More recent variations of the drama triangle have led to tools such as the ‘empowerment circle’ which identifies alternative roles to break the repetitive cycle of the drama triangle. The roles are paired as follows: villain – educator/consultant, victim – learner, rescuer – mediator/facilitator. It is suggested that, through the shifting of roles, there will be an accompanying shift in behavior and, ultimately, a different response will be elicited.

Davys, Allyson & Liz Beddoe, Best Practice in Professional Supervision: A Guide for the Helping Professions (London, UK: Jessica Kingsley Publishers, 2010).

Leave a Reply