This book examines supervision in the healthcare professions. Professional supervision in the health professions provides the core functions of accountability, education, and support. This book discusses four supervision models or approaches: developmental models of supervision, reflective models, post-modern approaches, and cultural supervision (see Chapter 2).

Developmental models of supervision consist of three categories: those that offer linear stages of development, those focused on process development models, and lifespan developmental models. These models follow the basic premise that practitioners follow a predictable, staged path of development and that supervisors require a range of approaches and skills to attend to each sequential stage as it is achieved.

Reflective approaches to supervision focus on the entire experience and the many dimensions involved, including the cognitive elements, feeling elements, meaning and interpretations from different perspectives. This process seeks to unsettle assumptions to alter practice and aid in understanding the connections between the public and private worlds.

Postmodern supervision approaches are strengths-based, solution-orientated, language-centered, and identity-focused. This model requires supervisors to approach supervision through a social constructionist lens. This includes supervision that emphasizes the way the participants in professional encounters construct meaning; focusing on strengths rather than weaknesses; acknowledging that there are multiple perspectives instead of universal truths; operating in less hierarchical ways; focusing on establishing collaborative approaches; and avoiding labelling individuals in a manner that highlights difference.

Finally, culturally based supervision considers how culture is relevant to the supervisor’s roles, style and skills. In this model, the supervisee’s working experience, training, and emotional needs are important, as are the emotional needs of the clients. Cultural supervision is linked to personal, family, community, cultural and professional domains. Supervisors should be trained in multicultural competency based on four dimensions: the awareness dimension (the supervisor must be aware of their own cultural and personal values; the knowledge dimension (facts and information about the history, world-views, culture codes, etc.); the relationship dimension (requires examination of supervision in cultural terms); and the skills dimension (the ability to intervene in a culturally sensitive way).

The book also discusses the role of power, trust, orientation toward learning, and continuing professional development within the supervisory relationship. The supervision relationship confers considerable authority on the supervisor, and potentially an overly comfortable relationship with the supervisee. This may lead to poor exercise of authority potentially amounting to collusion with the supervisee. This results in poor and unsafe practices. Thus, conversations about the power relationship are integral to the supervisory relationship, as are discussions about personal power. The supervisory relationship should be malleable to the changing and developing needs of the supervisor and supervisee. Both parties should acknowledge mutuality in the relationship and adapt to students’ learning orientation.

The book describes characteristics and skills of a good supervisor characteristics, including: competence and knowledge as practitioners, competence as supervisors, an ability to challenge in a supportive manner, openness to feedback, ability to be self-monitoring, ability to provide support and containment for a range of situations and emotions; an ability to manage power and authority, and to receive and value their own supervision. All of this must also take place within a context where supervisors are trained for their role.

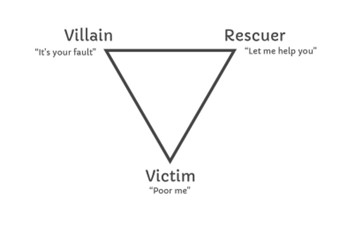

Finally, this book explores the emotional content of supervision. There are numerous barriers that prevent supervisors from the exploring feelings. These barriers include the expectations and limitations of professional and organizational culture, fear of being overwhelmed by the supervisee’s feelings, fear of exposing their own inadequacies, or feeling exposed and vulnerable to public criticism. Supervision may prioritize risk management over attention to the practitioner’s own process and affect. This is concerning because the awareness of one’s own emotions facilitates an awareness and understanding of the emotions of others. The emotional impact within supervision relationships, particularly those consisting of issues of inequality or power, may result in a ‘drama triangle’ (a model of dysfunctional social interactions), which consists of three roles: prosecutor, rescuer and victim, as reproduced below.

The drama triangle represents particular roles individuals hold in relation to others. The victim places responsibility and blame for situations onto the persecutor. The victim seeks a rescuer to save them from their unfair position. The prosecutor does not consider themselves responsible and places blame for failure on the victim. These roles are in constant flux, rendering solutions unachievable and problematic interactions replete. More recent variations of the drama triangle have led to tools such as the ‘empowerment circle’ which identifies alternative roles to break the repetitive cycle of the drama triangle. The roles are paired as follows: persecutor – educator/ consultant, victim – learner, rescuer – mediator/ facilitator. These roles involve seeking answers to questions about the situation and the resolution.

Allyson Davys & Liz Beddow, Best Practice in Professional Supervision: A Guide for the Helping Professions (UK: Jessica Kingsley Publishers, 2010).

Leave a Reply