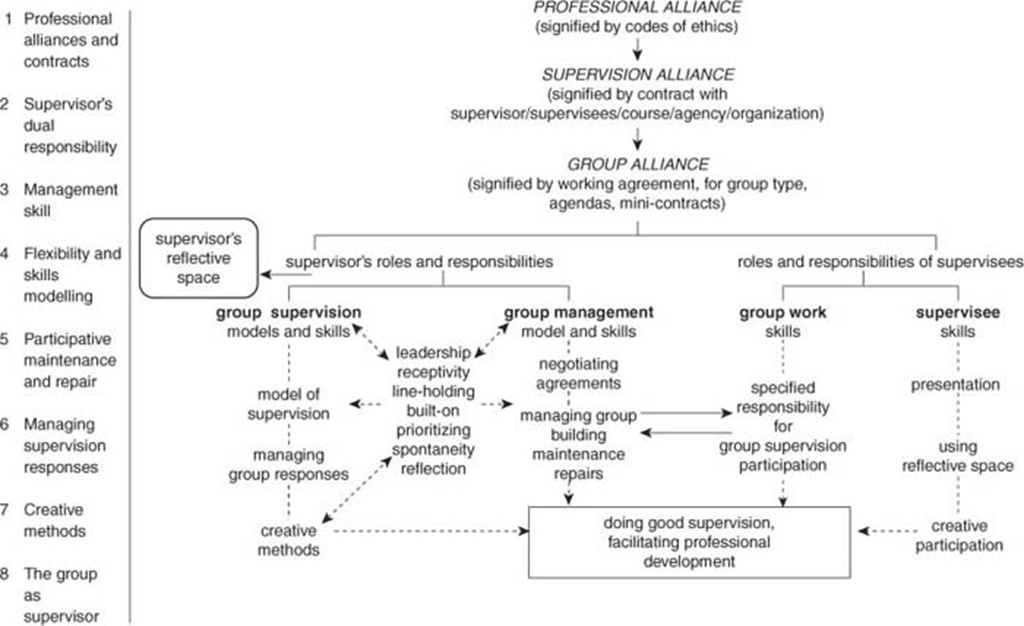

This book explores group supervision, a method of supervision that enhances supervisee skills including, courage and self-discipline, by way of the supervision alliance model (Inskipp and Proctor, 1995, 2001).

Brigid Proctor characterises the supervisor as:

“the person responsible for facilitating the counsellor, in role of supervisee, to use supervision well, in the interests of the client. His particular need is to have clarity about the task, so that he can be group manager as well as supervisor in a group. The role of group manager requires skills and abilities distinct from those of supervisor. Many will be transferable from other contexts. Some developed skills need to be left behind. The role entails sub-roles which may be in tension with each other” (ch 1).

“The supervisor has a dual responsibility. She is responsible for enabling and ensuring that good enough supervision is being done in the group. This responsibility carries with it the care for each individual’s learning and developmental needs. It may also carry managerial and training agendas, depending on the contract with any course or agency involved. At the same time, she is the leader in the group, at least at the outset. In her own style she needs to set the tone for the development of a culture of intention, empathic respect and straightforwardness – for a practical and effective group alliance” (ch 1).

Supervisors are required to have management skills, model flexibility and skill, and must manage and challenge the group to engage in its development, maintenance, and repair if required, manage free flow discussion, develop a sense of balance and timing within the group,

Unique to group supervision is that the supervisor and the participants must recognize that it is potentially the group that is the supervisor and “[a]s a supervisor it contains not only the resources of supervisor and each group member, but, in embryo, the rich creativity of a complex living group system” (ch 1). However, group sizes should not rise greater than six and no lower than four.

In addition to the supervisor, there are many stakeholders in group supervision, including professional bodies, clients, supervisees, supervisors, courses, organization, and agencies. In light of the variety of resources available, there is less likelihood of blind spots by supervisor and a supervisee.

“If group members can succeed in the task of doing ‘good supervision’, they will be able to weather anxieties about difference, and come to celebrate variations in style, beliefs, emotionality, competence, experience, gender, class, ethnicity and age – to name a few dimensions of conscious difference. They will have an added forum for noticing which differences of style, belief and practice they can accept and learn from, and which are in conflict with their beliefs and ethics and they want to challenge” (ch 2).

Brigid Proctor, Group Supervision: A guide to Creative Practice, 2nd ed, (London: Sage, 2008).

Leave a Reply